Feature

The Art of Packaging: A Measure of Royal Dignity

By Park Su-hee

Packing items for their protection or decoration is a long-standing practice in Korea. In particular, the royal family of the Joseon Dynasty paid careful attention to packaging, which was carried out using special materials in exclusive colors. When ceremonial objects were involved, the packaging of the times was itself considered a rite, known as bonggwa, and followed a rigorous set of procedures. The art of packaging for the Joseon royal house is explored below.

Dedicated Office for Packaging

The Sanguiwon (Royal Clothing Office) was established during the reign of King Taejo (r. 1392–98) as the organization responsible to the royal family for supplying and managing clothes, everyday necessities, and objects of regal authority. Until its abolishment in 1907, the Royal Clothing Office oversaw a wide range of royal items.

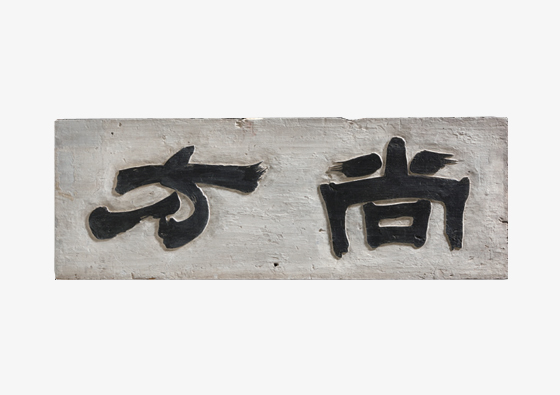

The name plaque for the Sanguiwon(Royal Clothing Office)

(collection of the NationalPalace Museum)

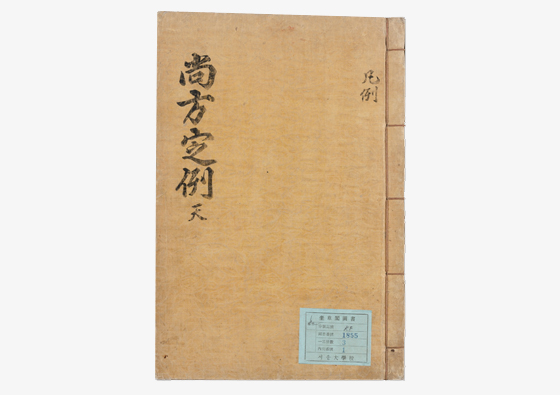

Sangbang jeongnye, the 18th-century book on rituals for royal attire

(collection of the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies)

The office adopted a diverse assortment of wrapping cloths and packing boxes according to the type and importance of the objects as a means to both ensure their protection and express royal dignity. Ceremonial robes for the king and crown prince, for example, were placed in red- and black-lacquered boxes, respectively, and stored at a building affiliated with the Royal Clothing Office called Myeonbokgak. The full process is recounted in detail in Sangbang jeongnye, the late-Joseon book on rituals for royal attire.

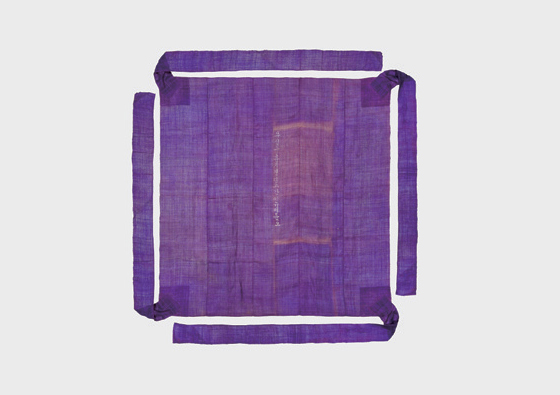

A single-layered wrapping cloth from the Joseon era

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

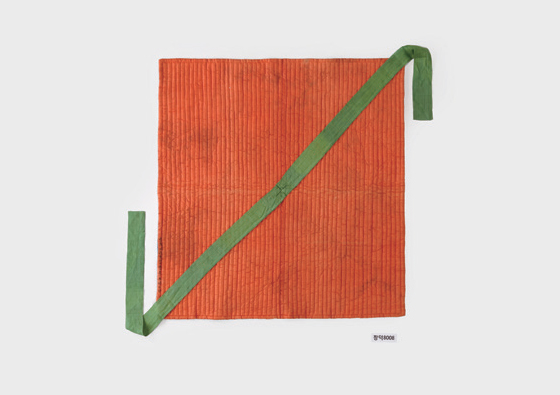

A quilted wrapping cloth from the Joseon era

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

A cotton-filled wrapping cloth from the Joseon era

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

An oiled paper-lined wrapping cloth from the Joseon era

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

Wrapping Cloths, A Primary Packaging Material

The Joseon royal family used diverse types of wrapping cloths as a principal outer packaging. Historical records describe the use of single-layered wrapping cloths for packing bedclothes and folding screens or covering chests . Double-layered wrapping cloths were mainly used for jewelry, quilted ones for fragile treasures, cotton-filled versions for items requiring support to maintain their forms (such as traditional hats and silver vessels), and wrapping cloths lined with oiled paper to seal dishes of food or

cover a dining table.

Wrapping cloths for the Joseon royal family came in diverse colors as well. For ceremonial objects, red was favored. Everyday necessities were wrapped in cloths of various colors, such as blue, black, navy, purple, and white. A double-layered wrapping cloth was made from two cloth pieces in contrasting colors for theaesthetic effect.

An early 20th century double-layered wrapping cloth for jewelry

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

An 18th century cloudand-treasure-patterned

wrapping cloth for a royal seal (collection of the National Palace Museum)

Traditionally made of silk, wrapping cloths could be plain or decorated with various patterns symbolizing royal authority and good fortune. Among other designs, clouds were commonly adopted as a decorative motif for wrapping cloths that packaged ceremonial seals. There are many examples of these cloud patterns applied in combination with treasure motifs in a great diversity of types and compositions. Cloud designs were also a decorative pattern of choice for the official costumes of high-ranking Joseon civil servants, testifying to its symbolism of dignity and authority.

Meanwhile, wrapping cloths for royal accouterments were ornamented with different auspicious patterns drawing on images of flowers, fruit, animals, and treasures.

Ornamental patterns could also be painted on the surface of the cloths. Reserved for special occasions such as royal weddings, painted wrapping cloths used a pair of phoenixes

in the center as a primary decorative pattern representing the king’s good governance. Notably, the phoenixes were surrounded by a lattice pattern or with small circles each

containing a propitious motif.

A fruit-patterned wrapping cloth from the Joseon era

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

A peony-and-scroll-patterned wrapping cloth from the

Joseon era (collection of the National Palace Museum)

Packaging of Ceremonial Objects

There is no better way to understand the art of Joseon royal

packaging than by exploring the packing process used for

material representations of regal authority, such as ceremonial

seals, ritual books, investiture edicts, and royal portraits. The

packaging of such objects demonstrating the exalted status

and dignity of members of the royal family was conducted

with dedicated rigor as a rite (bonggwa) attended by the highranking

officials involved in their production.

A phoenix-painted wrapping cloth from the Joseon era

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

The uigwe records on the marriage between King Yeongjo and Queen Jeongsun from the 18th century

(collection of the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies)

Royal Seals

A golden seal for Queen Jeongsun on the occasion of her

investiture as queen and the related packaging materials

Packaging materials for a royal seal consisted of a metal inner box, a wooden outer box lined with fish skin, a leather casket to contain the outer box, wrapping cloths for the seal and the boxes, and floss as a buffer. As a rule, the wrapping cloths were made from red silk of the highest quality available at the time and were embellished with gold leaf. After the royal family member to which it was dedicated died, the royal seal was enshrined in the Royal Ancestral Shrine (Jongmyo) alongside the spirit tablet.

Royal Books

A jade book for Ikjong (posthumously promoted to king status) and

the related packaging materials

Ceremonial royal books were fashioned by binding together several inscribed plates made of jade, bamboo, or gold. To package the book, cottonfilled wrapping cloths were first placed between the plates to absorb any friction. The book was enclosed in a silk case with buttons, wrapped in a cloth, and placed in an inner box. The space between the wrapped book and the inner box was stuffed with floss, and the box was locked. The locked box was inserted in an outer box and again wrapped in a cloth to complete the packaging process. The inner box in particular was ornamented by royal painters who created diverse motifs on the surface in gold powder mixed with glue.

The rendering process of a case for a jade book offered on the occasion of investiture ceremonies

Investiture Edicts

During the Joseon Dynasty, a royal edict was issued as an appointment certificate when someone was invested as queen, crown prince, or crown princess. The investiture edict was created by aligning five pieces of textile in red, yellow, navy, white, and black together, making it easily discernible from common official documents.

The 19th century investiture edict for Queen Hyohyeon

as the wife of King Heonjong and the related packaging materials

(collection of the National Palace Museum)

The 18th century packaging box for the investiture

edict for Crown Prince Sado as the heir to the

throne (collection of the National Palace Museum)

Rendered in the form of a handheld scroll, the investiture edict was first wrapped in silk cloth and fastened with lace, then placed in a red- or blacklacquered box with the space between the box and the contents stuffed with floss. Fragrant incense was added to drive off insects, and the box was secured by a lock with the key kept separately in a pouch. For the packaging of investiture edicts, red silk was the cloth of choice, and as with the inner box for a ceremonial book the packing box would be lavishly decorated with motifs including dragons, bamboo, and orchids.

Gukjo bogam (Exemplary Achievements of the Preceding Monarchs)

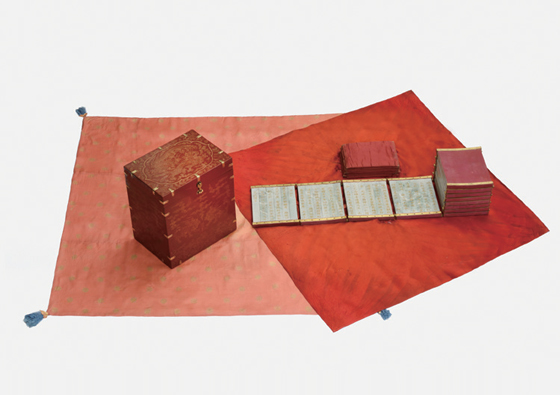

Gukjo bogam (Exemplary Achievements of the Preceding Monarchs) from 1909

and the related packaging

materials (collection of the National Palace Museum)

Gukjo bogam (Exemplary Achievements of the Preceding Monarchs) is a collection of 28 books on the laudable accomplishments of the Joseon kings chronologically organized according to the reign of each ruler. The initial books (each consisting of several volumes) were completed in 1457 during the reign of King Sejo, the seventh ruler of Jose on, and the publication of preceding kings’ achievements continued until 1939 with different versions being made for specific purposes. There were versions for dedication to the incumbent king, distribution to major government agencies and individuals, and for enshrinement in Jongmyo. Among them, the ones to be enshrined in the ancestral shrine for the royal family were treated with special care. These were packed following a solemn set of procedures and carried to the shrine in a palanquin.

The compilations of Gukjo bogam published in 1909 for Jongmyo enshrinement, currently housed at the National Palace Museum of Korea, have been transmitted to the present alongside their packing materials, including the inner wrapping cloth, the box for the wrapped books, a lock for the box, the outer wrapping cloth for the locked box, and the lace used to once again fasten the wrapped box.

Royal Portraits

During the Joseon Dynasty, portraits were produced in great numbers under

the auspices of the royal family. These were not only of the king and his family

members, but also of meritorious officials for endowment. Closely associated with

royal legitimacy and authority, a portrait of the king was produced in accordance with

solemn procedures under the supervision of the

king himself. Considered to be the equivalent of

the living king, his painted representations were

elaborately packaged when not in use or on the

move between locations. Royal portraits were

housed in a separate building, called Seonwongak.

A completed royal portrait was first wrapped in

two layers of cloth, one white and one red, and

placed in a red textile case. It was then encased in

a black-lacquered box along with fragrant incense

and secured with a lock. As a finish, it was once

again covered in a protective casket. During the

reign of King Sukjong (r. 1674–1720) a leather case

and a black-lacquered container were created for

the emergency transportation of royal portraits.

A black-lacquered box and protective casket for a royal

portrait from the Joseon era (collection of the National Palace Museum)

A leather casket and a black-lacquered container for a royal

portrait from the Joseon era (collection of theNational Palace Museum)