Interview

Finding Connection through Bamboo Blinds

By Choi Min-young

Interview with Master Jo Dae-yong and

the architects Jang Young-chul and Chun Sook-hee

Koreans have long possessed a special method for blocking out the sweltering summer heat: bamboo blinds, or bal in Korean. Bamboo screens filter out strong sunrays but allow in the breeze. They can divide a space without hindering communication. They have long been an important element in Koreans’ everyday lives, and in rituals as well. The traditional bamboo-screen maker Jo Dae-yong and the architects Jang Young-chul and Chun Sook-hee, who have creatively applied the craft of bamboo-screen making to architectural structures, share their thoughts on this traditional Korean handicraft.

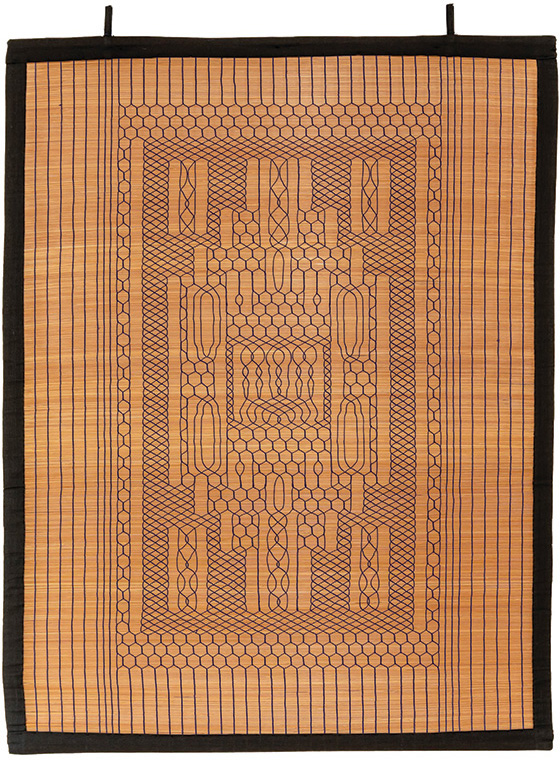

The tortoise-shell design preferred by Master Jo (67 x 85cm; photo courtesy of Jo Dae-yong)

A Connective Barrier for Sunrays

Bal, or bamboo screens, are closely associated with the layout of traditional Korean houses. Every traditional Korean house (hanok) has a room with a wooden floor in the middle that is exposed to the outer areas. This open structure allows warm sunlight and refreshing breezes to enter the house. However, it can also let in unwanted influences from the outside. Bamboo screens are nicely suited to the open layout of a traditional Korean house.

“A bamboo screen minimizes the impact of a strong sunlight, but still permits air movement. It provides privacy indoors, but allows a glimpse of the outside. It partitions space, but without creating a stuffy sense of isolation. If you have a bamboo screen, you can open your door wide on a summer day and enjoy the breeze without worrying about gazes from the outside.”

A bamboo screen was affixed in front of the throne or in the living quarters of the queen as a device to prevent any inadvertent viewing of the royal face of the king or queen. The queen mother remained behind a bamboo screen when she ruled as regent on behalf of a young son. This kind of political practice was referred to as suryeom cheongjeong, or “ruling behind the bamboo screen.”

The major material for Korean bamboo screens is, in fact, bamboo. Jo Dae-yong, the nationally designated master of bamboo-screen making, uses Simon bamboo that grows in the coastal area of Tongyeong in the southern section of the country.

“Simon bamboo is a relatively thin-stemmed bamboo that is commonly used for making arrows and tobacco pipes. Bamboo culms with thick stems leave obvious marks from their joints in a bamboo screen. Simon bamboo is free from such noticeable joints, and therefore is more suitable as a material for blinds. This species of bamboo is also soft and flexible but maintains great durability.”

Master Jo must collect a year’s supply of bamboo in December and January. Summer is a poor season to gather bamboo since it is exposed to attack from insects. The collected bamboo stems are stripped of their outer skins with a knife and divided lengthwise into six or eight pieces. They are dried under the sun for 45 days, at which point the sun-bleached bamboo pieces are split again into 1-millimeter strips. These are then run through even smaller holes made in an iron plate.

“A 1-millimeter-wide bamboo strip is reduced to 0.8 millimeters after passing through this hole. It is shaved to 0.7 millimeters in the next, and 0.6 millimeters in the final hole. Bamboo strips that are wider than 0.6 millimeters in diameter are not suitable for weaving bamboo screens. One bamboo blind requires 1,800–2,000 individual strips; this means running bamboo strips through iron holes 6,000 times.”

Once bamboo strips of the appropriate size are ready, spools of thread are hung on a weaving frame. A complex motif requires additional spools. Now, the weaving can begin. Threads are passed above and under the bamboo strips functioning as the warp to create the intended design. However nimble the maker may be, no less than 100 days are required to finish a single bamboo blind.

“Korean bamboo blinds are flamboyant, but possess a gentle aesthetic. They are not boastful, but gradually exude beauty. It is like you do not realize there is a woven motif in the bamboo screen at first, but one year later the design suddenly captures your attention. Depending on the perspective from which you look at it or where you hang it, the bamboo screen can give different sensations.”

The decorative pattern Master Jo prefers is a tortoise-shell design. This hexagonal design symbolizing longevity is beautiful to the eye and also contributes to tightly binding the component bamboo strips. His bamboo blinds are both graceful and powerful.

Bamboo strips are run through the holes in an iron plate; spools of thread are prepared, the number of which varies with the size of the bamboo screen and the complexity of an intended design (photo courtesy of the National Intangible Heritage Center).

Master of Bamboo-blind Making Jo Dae-yong

Master Jo Dae-yong is making dedicated efforts to sustain

the craft of bamboo-screen weaving

(photo courtesy of the National

Intangible Heritage Center).

Bamboo-blind weaving is Jo’s family vocation. His great grandfather supplied bamboo blinds to the Joseon court. His bamboo screens were highly lauded by King Cheoljong (r. 1849–63). Jo’s grandfather and father also worked in this tradition. Jo Dae-yong first experienced bamboo craft as an elementary school student. After completing his military duty in his early 20s, Jo dedicated himself to bamboo-screen making. He gradually built a name for himself, and in 1992 was designated the national master of bamboo-blind weaving, National Intangible Cultural Heritage No. 114.

“When I received a request to restore the bamboo blind that once hung in the T-shaped shrine of Yeongneung Tomb, I went to the royal tomb and examined the shrine. There were devices installed along the upper edge of the doorframe that were used to hold a bamboo screen. Considering that blinds crafted for this purpose weighed as much as 15 kilograms, these kinds of supporting devices must have been necessary. I checked another royal tomb, Seolleung, and the shrine there also had these devices. The same was true for the royal ancestral shrine of Jongmyo.”

The bamboo blind for Yeongneung, the tomb of King Sejong, the fourth ruler of Joseon, was reborn in his hands. Master Jo also performed repair work on the bamboo screens at Jongmyo, where the spirit tablets of the Joseon monarchs are enshrined in individual spaces. There are about 100 bamboo screens in Jongmyo. The most recent project Master Jo was charged with was the restoration of the red bamboo screens in Hamnyeongjeon Hall at Deoksugung Palace, where Emperor Gojong spent the last days of his life prior to his death on January 21, 1919. Equipped with the three restored blinds 292 centimeters wide and 320 centimeters high, the royal building seems to have reclaimed the authority and dignity it possessed during the reign of Emperor Gojong.

“There were more than 20 bamboo-screen makers for the Joseon court: this indicates the importance of the craft at the time. I think we need to make more substantive efforts at the restoration of the tradition. There are 42 royal tombs on the Korean Peninsula. It is my dream to restore all of the bamboo blinds in these royal tombs.”

Restoring the past does not just mean the reinstitution of its material components. It also includes the effort needed to keep its intangible aspects alive. Jo Dae-yong and other masters of traditional skills dedicate their lives to preserving and revitalizing intangible elements of the past. Equally important to maintaining traditional skills is the creative work of reinterpreting them in contemporary sociocultural contexts. The architects Jang Young-chul and Chun Sook-hee at Wise Architecture embodied traditional Korean bamboo screens into the façade of a building.

Hamnyeongjeon Hall at Deoksugung Palace with the three red bamboo screens Master Jo restored in 2016 (photo taken by Guru Visual Inc. and provided by Areumjigi)

A Link between Architecture and Craft

From the left, Chun Sook-hee and Jang Young-chul at Wise Architecture

(photo courtesy of Jung Meen-young)

Bukchon is a hilly neighborhood of traditional houses located between Gyeongbokgung and Changdeokgung royal palaces. Midway up Gahoe-ro street in Bukchon is a notable building with a striking appearance. It houses Dialogue in the Dark, an exhibition that offers the chance to experience everyday environments in the dark without recourse to sight.

“Dialogue in the Dark is an experiential exhibition that was initiated by Dr. Andreas Heinecke of Germany and has been shared by more than 10 million people in 32 countries. This is the first dedicated exhibition building for it in the world. When we designed this structure, we delved into the question of what could connect such keywords as ‘darkness,’ ‘Bukchon,’ and ‘tradition.’ We found the answer in traditional Korean bamboo blinds.”

The bamboo blinds are integral to the building. Its façade is composed of 27 elements evocative of bamboo screens. The façade made of bamboo blinds foregrounds the traditional characteristics of the Bukchon area and also delivers the essential theme of the exhibition—an experience without light. This bamboo-blind façade also amplifies the auditory effects of rain and wind.

“Bamboo blinds shield the light and obscure the image of that which exists beyond them. In this building, the bamboo screens on the façade symbolize the experience of everyday life in darkness, the main message of the exhibition.”

The bamboo screen elements comprising the face of the building are not made of bamboo, however. The designers chose to translate this tradition for modern uses. Aluminum sheets were cut with a water jet to create component strips possessing a rough texture matching that of actual bamboo strips, and these aluminum strips were connected with acetal beads one by one, just like bamboo strips are interwoven with threads.

“Bamboo is such an attractive material for architecture. Without much work, you can produce lengthy architectural members. They grow fast, so there is little worry about supply. However, bamboo stems are rich in moisture and therefore vulnerable to the growth of mold. The Dialogue in the Dark building borrows from traditional bamboo blinds only their texture and function. A bamboo screen physically divides an area and creates a boundary to vision, but it still connects the space throughout. Through the metaphor of a bamboo screen, we wanted to say that we are within a single space and can still communicate with each other.”

The façade of the Dialogue in the Dark building in Bukchon, Seoul (photo courtesy of Kim Yong-kwan)

A Modern Translation of Tradition

Whenever a new building is constructed in the Bukchon area, it is required to reflect traditional Korean sensibilities in its design so that it can harmonize with the surrounding architectural environment. This explains the dominance of houses with traditional tiled roofs in this area. Faced with these regulations, the architects Jang and Chun did not see an easy way out. Given its target visitors and the fact that the planned building was an exhibition space, the image of a traditional Korean house did not match up in their minds. During their artistic investigation into how to dress a building with a modern purpose in a traditional way, they extended their exploration from architecture to craft and finally found a satisfying solution in traditional bamboo blinds.

“When we work on new buildings in the areas around the royal palaces, I am always asked about whether they will blend well with the traditional architecture of the palaces. The royal compounds were built using the state-of-the-art skills and techniques of the time. Rather than clinging to roof tiles or wooden pillars and beams, we’d be better off recognizing that what we are doing today is part of history and tradition.”

When the relationship between tradition and architecture is freely explored rather than obsessively concentrating on traditional architecture per se, tradition allows various interpretations and enables a transition to modern creations. Jang Young-chul and Chun Sook-hee believe that complementing and reimagining what has been transmitted is part of what is required of architects.

“An increasing number of early-modern buildings have been registered on government heritage lists. This means that the buildings that are part of our everyday lives or have been closely associated with our memories can become something to preserve and protect as heritage. Yes, architecture is part of our memories. We, as architects, need to think hard about how to utilize or preserve these architectural manifestations of our memory.”

The same is true of the transmission of tradition. Tradition is not fixed in a particular point in time, but a process under which what has been passed down to the present is continuously created and recreated for the future. This must be kept in mind by contemporary Koreans as they pass along traditions.

The Dark in the Dialogue building seen from the inside looking out(photo courtesy of Kim Yong-kwan)

Text by Choi Min-young

Photos by the National Intangible Heritage Center; Master Jo Dae-yong; Arumjigi Culture Keepers Foundation; Wise Architecture; Kim Yong-kwan, Archilife Publishing Company; and Jung Meen-young, photographer

발, 通하다

국가무형문화재 조대용, 건축가 장영철·전숙희

뜨거운 여름, 들이닥치는 볕을 거르고 선선한 바람은 드나들게 하여 여름의 가혹함을 가라앉히는 한국의 비법이 있다. 은근하고 고혹한 멋으로 계절을 풍성하게 하고, 공간을 가르되 그 너머의 존재를 인식할 수 있어 공존을 깨닫게 하는 그것은 한국인의 일상은 물론 의례까지 아우른다. ‘발’이다. 전통의 기법으로 발을 짜는 국가무형문화재 조대용 선생과 전통 발을 건축물의 상징으로 접목한 와이즈 건축의 장영철·전숙희 소장을 만났다.

발, 운치를 드리우다

발은 전통 한옥 구조와 함께 해온 가림막이다. 한옥은 집의 중심인 마루로 빛과 바람이 그대로 드나드는 개방형 구조를 가졌다. 이는 자연을 집안으로 끌어들인다는 장점을 갖고 있지만, 외부의 각종 요소들이 침투하는 단점이 되기도 한다. 발은 이러한 결점을 가장 현명하게 보완한다.

“발을 햇볕을 가리되 바람은 통하고, 실내를 가리되 상대적으로 환한 바깥은 볼 수 있으며 공간을 가르되 벽이 아니니 답답하지 않죠. 더운 날 방문을 활짝 열어놓아도 지나가는 사람과 눈 마주칠 걱정 없이 시원하게 바람을 즐길 수 있습니다.”

이러한 특징으로 하여금 발은 궁궐에서 더욱 특수한 임무를 수행한다. 임금이 앉는 용상이나 왕비의 처소 등에도 반드시 발을 쳐 함부로 얼굴을 볼 수 없게 하고, 어린 임금 뒤에서 대비나 대왕대비가 정사를 돌볼 때에도 그 사이에 발을 쳐 존재감을 표했다. 이러한 형태의 정사를 ‘수렴청정(垂簾聽政)’이라 일컫는데, 이 말에 들어있는 렴(簾) 자가 바로 발을 뜻한다. 공간을 가르지만 완벽히 차단하지는 않는 발의 기능이 사회적 관습을 상징하는 하나의 오브제가 된 셈이다.

우리나라의 발은 주로 대나무를 재료로 하고 갈대, 삼, 달풀 등을 이용해서도 만들었다. 조대용 선생은 통영 바닷가에서 나는 해장죽을 재료로 하여 발을 엮는다.

“해장죽은 주로 화살이나 담뱃대를 만드는 데 쓰인 가는 대나무입니다. 왕대로 발을 짜면 대나무 마디가 보이는데 반해 해장죽은 그 마디가 크게 두드러지지 않아 깔끔하죠. 가늘고 부드러운데다 탄력성이 좋아서 잘 부러지지 않습니다. 내구성이 아주 좋은 재료입니다.”

조대용 선생은 나무의 휴면기간인 12월과 1월 사이 1년 동안 쓸 해장죽을 채취한다. 여름에는 벌레가 나무 속을 다 갉아먹어 못쓴다. 채취한 해장죽은 겉껍질을 칼로 훑어 벗겨내고 6~8등분 하여 45일간 말린다. 연한 미색으로 탈색된 해장죽을 1mm 두께로 쪼개어 쇠판에 낸 구멍 사이로 훑어 다시 굵기를 조정한다.

“큰 구멍을 한번 통과하면 대오리 지름이 0.8mm가 되고, 한 번 더 작은 구멍을 통과하면 0.7mm가 됩니다. 그리고 또 한 번 통과하면 0.6mm가 되죠. 그 정도 두께가 되어야 발을 엮어요. 발 하나를 짜려면 1800~2000개 정도의 대오리가 필요하니까 6000번은 이 작업을 하는 겁니다.”

대오리가 준비되면 대오리를 서로 엮을 실을 채비한다. 실을 감은 실패 모양의 고드래를 발틀에 촘촘히 걸어둔다. 발에 넣을 문양이 복잡할수록 고드래도 많이 필요하다. 이제 대오리라는 날실에 명주실을 씨실 삼아 한 올 한 올 엮어간다. 빠르고 정확한 손놀림으로 부지런히 엮어도 하나의 발을 완성하기 까지 100일이라는 시간이 필요하다.

“우리 발은 화려하지 않지만 은은한 멋이 있습니다. 앞서서 자신의 아름다움을 뽐내는 것이 아니라 문양이 있는지 조차 눈치채지 못하다가 일 년 이 년 바라보면 그 문양이 비로소 눈에 들어옵니다. 각도에 따라 물결이 보이기도 하고, 발을 치는 위치에 따라 그 빛도 달라지지요. 꼭 옛 선비들 같다는 생각이 듭니다.”

그의 대표적인 문양은 귀갑문, 그러니까 거북등딱지의 6각 문양이다. 무병장수를 상징하는 이 문양은 사실 대오리간의 결속력을 강하게 하는 데에도 한몫 한다. 그리고 완성된 모습 또한 독특하고 아름답다. 특히 그의 손이 닿은 발은 강인한 동시에 우아하다.

조대용, 잠든 나라를 흔들어 깨우는 사람

조대용 선생의 집은 대대로 발을 짰다. 증조할아버지가 철종 임금께 진상한 발은 큰 칭찬을 받았다. 할아버지와 아버지를 이어 조대용 선생도 초등학교 시절부터 발을 짰다. 군대에 다녀온 후에 용돈벌이 삼아 본격적으로 발을 짜기 시작했는데 그에게 발을 주문하는 사람이 있을 정도로 유명해졌다. 1983년 한국문화재보호협회 이사장상 수상을 시작으로 꾸준한 노력 끝에 1992년 국가무형문화재 제114호 염장에 이름을 올렸다.

“영릉 정자각(제사 지내는 곳)의 신렴을 복원하자는 제의를 받았어요. 직접 가서 보니 위쪽 문 틀에 발을 걸어두는 축과 그 발을 고정해두는 고리가 있더군요. 여기에 쓰는 발은 두툼한 대나무로 만들기 때문에 발의 무게가 15kg이나 됩니다. 이 무게를 감당하려면 그런 장치가 꼭 필요했던 것이죠. 혹시나 하여 선릉에도 찾아가보니 똑같은 장치가 있었습니다. 종묘에도 마찬가지였죠.”

그의 손길로 종묘와 세종대왕의 능인 영릉 정자각(제사 지내는 곳)의 신렴이 되살아 났다. 조선의 임금과 왕후의 신주를 모신 왕실 사당 종묘에는 각각의 공간을 나누고 외부의 시선을 거르는 데에 필요한 주렴이 100개에 이른다. 훼손된 발을 수리하고 보완하여 일정한 모양새를 갖추어 놓았지만, 조금 더 적극적인 복원이 필요하다는 것이 그의 의견이다. 최근에는 고종이 승하할 때까지 지냈던 덕수궁 함녕전의 붉은 외주렴을 복원했다. 폭 292cm, 높이 320cm 외주렴 3개를 되찾은 함녕전은 그 위엄과 아취마저 살아나 척추를 곧게 세운 듯 꼿꼿해 보인다.

“옛 궁궐에는 스무 명이 넘는 염장이 있었어요. 그만큼 발 만드는 일을 중요하게 여겼습니다. 이제 문화재들의 외형을 복원하는 일에서 더 나아가 그 내부도 충실히 해야 할 때라고 생각합니다. 우리나라에 42기의 왕릉이 존재합니다. 그곳들의 신렴을 모두 복원하는 것이 저의 꿈입니다.”

한동안 사라졌던 전통을 복원한다는 것은 당시의 자연환경이나 생활 방식, 사회적 배경과 관습까지 되살린다는 것이다. 아무리 발달된 과학기술을 가졌다 해도 자연의 순리대로 살았던 옛 사람들의 삶이 오늘날에 그대로 돌아오는 것은 불가능하다. 국가무형문화재의 존재가 중요한 이유가 여기에 있다. 전통의 기법을 고스란히 다음 세대에 잇기 위해 조건 없이 자신의 평생을 바친 그들의 숭고한 헌신이 필요하다. 더불어 이렇게 끊임없이 이어지는 전통의 기법을 현대적 문법으로 상상하고 실현하는 이들의 노력 또한 중요하다. 우리의 전통 발을 건물의 외벽으로 표현하여 그 상징과 의미를 현실화한 이들이 있다. 와이즈 건축의 장영철·전숙희 소장이다.

건축과 공예의 가름선을 지우다

서울 북촌의 가회로는 구릉으로, 걸어 오르려면 어느 정도의 근력이 필요하다. 한옥과 현대식 건물의 오묘한 조화로 이루어진 이 언덕길의 중턱까지 오르면 조금 독특한 외관의 건물이 보인다. 전시 공간 ‘어둠 속의 대화(Dialogue In The Dark, 이하 DID)’다. 이 곳은 시각이 차단된 어둠 속에서 일상을 체험하는 전시 공간으로 경험과 기억을 통해 공간을 인지할 수 있도록 설계되어 있다.

“독일 안드레아스 하이네케 박사(Dr.Andreas Heinecke)에 의해 시작된 어둠 속의 대화는 세계 32개의 국가에서 천만 명 이상의 이용자가 함께 한 체험 전시입니다. 전용관이 지어진 것은 한국이 최초입니다. 이 곳의 설계를 위해 ‘어둠’, ‘북촌’, ‘전통’이라는 맥락을 잇는 방식이 필요했고, 이에 대한 답을 우리 전통의 발에서 찾았습니다.”

발의 형태는 건물 외벽에 고스란히 담겨있다. 건물의 전면을 27개의 대형 발로 형상화 한 것. 이 발은 북촌의 지역적 특징을 반영하는 동시에 시선을 적절히 차단하는 블라인드 역할을 하며 전시 성격을 드러낸다. 비가 내리거나 바람이 불면 그 소리들을 고스란히 청각화하는 효과도 있다.

“발에는 빛을 차단한다는 주요 기능이 있지만, 이 건물에서는 어둠 속에서 일상을 체험한다는 전시의 성격을 전면에 드러내는 장치로서의 기능이 더 큽니다. 발 너머의 이미지를 투영하고 빛을 투과할 뿐 그 안에 무엇이 있는지는 선명하게 보이지 않죠.”

와이즈 건축은 이 전통의 발을 기능과 현대적 형태로 치환하기 위해 알루미늄을 가공해 워터젯으로 울퉁불퉁한 질감을 살려 재단하고, 각 가닥들에 구멍을 뚫어 아세탈(acetal) 구슬로 한 땀씩 꿰고 엮었다. 발을 만들기 위해 대나무를 숱하게 깎고 명주실로 촘촘히 이은 작업 방식을 건축의 개념에도 적용한 것이다.

“대나무는 대단히 매력적인 건축 재료입니다. 특별한 가공 없이도 수직으로 뽑아내는 데에 유리하고, 그래서 자연의 느낌 그대로를 건축에 반영할 수 있죠. 또 성장이 빨라 수급도 좋습니다. 그러나 수분이 많아서 곰팡이가 좋아한다는 점은 치명적인 단점이지요. DID의 발은 대나무라는 재료의 질감과 그 쓰임새만 가져왔어요. 공간과 공간을 갈라 시선적 경계를 만들되 완전히 차단하지는 않아 우리는 같은 공간 안에서 함께 소통하는 사람입니다, 라는 공감대를 끌어낼 수 있다는 점에 착안했어요.”

와이즈 건축, 시대를 가르되 역사는 가르지 않는

북촌은 건축물을 새로 지을 때 주변 경관, 지역적 특성을 고려하여 한국적인 감각을 반영해야 한다는 특별한 과제가 있다. 대부분의 건축물이 머리 위에 기와를 얹고 있는 것도 그런 이유이다. 하지만 와이즈 건축에서는 쉬운 답을 내고 싶지 않았다. 이 건물의 이용자, 전시공간이라는 쓰임새를 생각했을 때 한옥의 방식과는 거리가 멀었고, 그렇다면 현대적 건축물에 전통의 옷을 어떻게 입힐 것인가가 관건이었다. 그들은 건축기법이 아닌 전통 공예로 시선을 확장했고, 마침내 빛을 조절하고 공간을 가르는 발을 떠올렸다.

“궁궐과 인접한 곳에 건물을 지을 때 ‘궁궐과 어울리나요?’라는 질문을 늘 받곤 해요. 궁궐은 당시 최고의 기술력과 최신의 개념을 적용한 곳이에요. 기와나 목구조만을 전통기법이라 하면, 지금 우리의 지금은 어디에 기록되어 남겨질까요. 한국 전통이 가진 공통분모는 한국인, 한국인의 생활 방식, 그리고 한국인이 살아가는 이 땅이에요. 현대를 살아가는 우리도 역사를 쓰고 있고, 지금 이 시간도 역사의 한 과정이라는 것을 잊지 않았으면 해요.”

우리는 고정관념을 경계해야 한다. 전통과 건축을 연결할 때, ‘한옥’의 건축적 특징에서만 답을 찾으려 하기 보다 더 넓은 의미를 살펴보아야 우리의 전통이 다각도에서 해석되고 또 현대적 감각으로 이어질 수 있을 것이다. 와이즈 건축은 현재의 건축가의 역할에 기존의 것들을 어떻게 보완할 것인지 고민하는 역할을 보태야 한다고 했다. 기존의 건축물을 어떻게 해소하고, 기존의 도시를 더 살기 좋은 도시로 만들기 위해 건축가의 움직임이 확장되어야 한다고.

“최근 건축문화재로 등록되는 건물들이 늘고 있습니다. 평범한 건물이라고 생각했는데 우리 삶에 깊이 들어와 있는 경우나 아픈 역사의 한 자락을 상징하는 건물도 문화재로 지정되기도 하죠. 이처럼 건축을 우리가 함께한 기억이라고 여긴다면 건축의 할 일이 점점 많아집니다. 이러한 건물들을 우리가 어떻게 활용하고 보존할 것인가에 대한 고민이 필요한 때입니다.”

우리가 전통의 맥을 잇기 위해 고민하는 것도 궤를 같이 한다. 전통이 전통이라는 이름으로 한 시점에 묶여있는 것이 아니라 오늘과 내일에도 함께 살아 숨쉴 수 있도록 고민하는 것. 그것이 지금 우리가 해야 할 일이 아닐까.

Interview 국가무형문화재 조대용 & 건축가 장영철·전숙희

Text by 최민영

Photos by 조대용, 국립무형유산원, 재단법인 아름지기, 김용관, 정민영